7 min to read

Kubernetes Up & Running (Chapter-1)

Kubernetes

In this series of articles, I wanted to share the important parts from the Kubernetes Up & Running book. First of all, I would like to thank Brendan Burns, Joe Beda and Kelsey Hightower who contributed to this book.

What is Kubernetes and why we need it?

Kubernetes is an open source orchestrator for deploying containerized applications. It was originally developed by Google, inspired by a decade of experience deploying scalable, reliable systems in containers via application-oriented APIs. It provides the software necessary to successfully build and deploy reliable, scalable distributed systems.

You may be wondering what we say “reliable, scalable distributed systems”. More and more services are delivered over the network via APIs. These APIs are often delivered by a distributed system, the various pieces that implement the API running on different machines, connected via the network and coordinating their actions via network communication. Because we rely on these APIs increasingly for all aspects of our daily lives, these systems must be highly reliable.

Benefits:

- Velocity

- Scaling (of both software and teams)

- Abstracting your infrastructure

- Efficiency

Velocity

Velocity is measured not in terms of the raw number of features you can ship per hour or day, but rather in terms of the number of things you can ship while maintaining a highly available service.

In this way, containers and Kubernetes can provide the tools that you need to move quickly, while staying available. The core concepts that enable this are:

- Immutability

- Declarative configuration

- Online self-healing systems

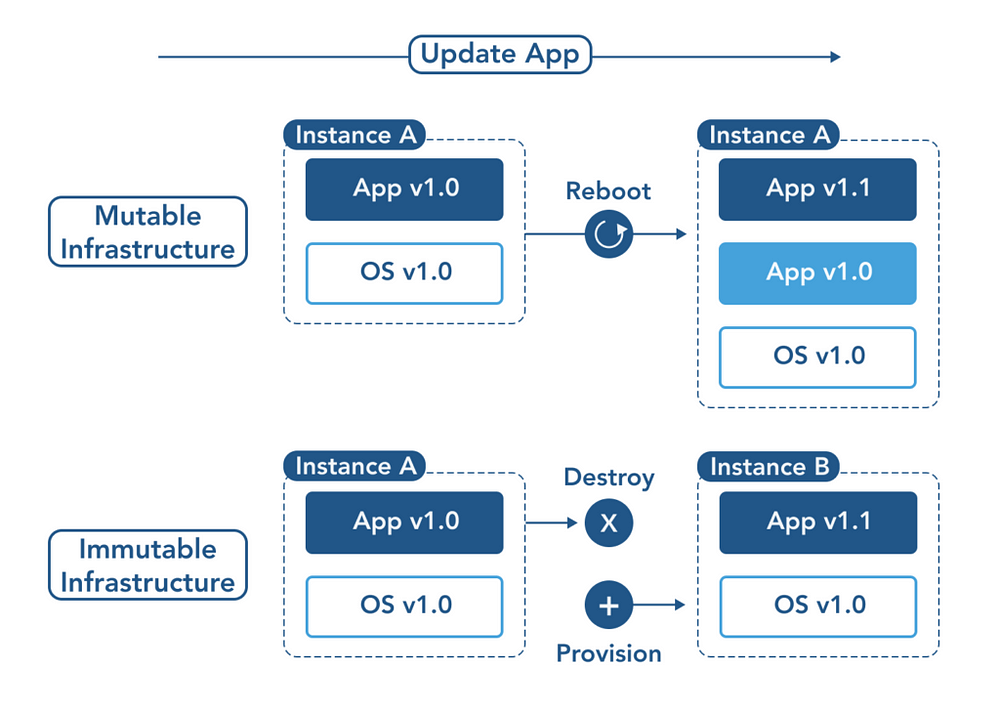

The Value of Immutability

A system upgrade via the apt-get update tool is a good example of an update to a mutable system. Running apt sequentially downloads any updated binaries, copies them on top of older binaries, and makes incremental updates to configuration files.

In contrast, in an immutable system, rather than a series of incremental updates and changes, an entirely new, complete image is built, where the update simply replaces the entire image with the newer image in a single operation. There are no incremental changes.

To make this more concrete in the world of containers, consider two different ways to upgrade your software:

- You can log in to a container, run a command to download your new software, kill the old server, and start the new one.

- You can build a new container image, push it to a container registry, kill the existing container, and start the new one.

Additionally, building a new image rather than modifying an existing one means the old image is still around, and can quickly be used for a rollback if an error occurs. In contrast, once you copy your new binary over an existing binary, such a rollback is nearly impossible.

Declarative Configuration

Everything in Kubernetes is a declarative configuration object that represents the desired state of the system. It is the job of Kubernetes to ensure that the actual state of the world matches this desired state. Much like mutable versus immutable infrastructure, declarative configuration is an alternative to imperative configuration, where the state of the world is defined by the execution of a series of instructions rather than a declaration of the desired state of the world. While imperative commands define actions, declarative configurations define state.

Because it describes the state of the world, declarative configuration does not have to be executed to be understood. Its impact is concretely declared. Since the effects of declarative configuration can be understood before they are executed, declarative configuration is far less error-prone. Further, the traditional tools of software development, such as source control, code review, and unit testing, can be used in declarative configuration in ways that are impossible for imperative instructions. The idea of storing declarative configuration in source control is often referred to as “infrastructure as code”.

Self-Healing Systems

Kubernetes is an online, self-healing system. When it receives a desired state configuration, it does not simply take a set of actions to make the current state match the desired state a single time. It continuously takes actions to ensure that the current state matches the desired state. This means that not only will Kubernetes initialize your system, but it will guard it against any failures or perturbations that might destabilize the system and affect reliability.

Self-healing systems like Kubernetes both reduce the burden on operators and improve the overall reliability of the system by performing reliable repairs more quickly.

As a concrete example of this self-healing behaviour, if you assert a desired state of three replicas to Kubernetes, it does not just create three replicas, it continuously ensures that there are exactly three replicas. If you manually create a fourth replica, Kubernetes will destroy one to bring the number back to three. If you manually destroy a replica, Kubernetes will create one to again return you to the desired state.

Online self-healing systems improve developer velocity because the time and energy you might otherwise have spent on operations and maintenance can instead be spent on developing and testing new features.

Scaling

Kubernetes achieves scalability by favoring decoupled architectures. In a decoupled architecture, each component is seperated from other components by defined APIs and service load balancers. Decoupling components via load balancers makes it easy to scale the programs that make up your service, because increasing the size(and therefore the capacity) of the program can be done without adjusting or reconfiguring any of the other layers of your service.

Decoupling servers via APIs makes it easier to scale the development teams because each team can focus on a single, smaller microservice with a comprehensible surface area.

Because your containers are immutable, and the number of replicas is merely a number in a declarative config, scaling your service upward is simply a matter of changing a number in a configuration file, asserting this new declarative state to Kubernetes, and letting it take care of the rest.

One of the challenges of scaling machine resources is predicting their use. If you are running on physical infrastructure, the time to obtain a new machine is measured in days or weeks. On both physical and cloud infrastructure, predicting future costs is difficult because it is hard to predict the growth and scaling needs of specific applications. Kubernetes can simplify forecasting future compute costs.

Kubernetes provides numerous abstractions and APIs that make it easier to build these decoupled microservice architectures:

- Pods, or groups of containers, can group together container images developed by different teams into a single deployable unit.

- Kubernetes services provide load balancing, naming, and discovery to isolate one microservice from another.

- Namespaces provide isolation and access control, so that each microservice can control the degree to which other services interact with it.

- Ingress objects provide an easy-to-use frontend that can combine multiple microservices into a single externalized API surface area.

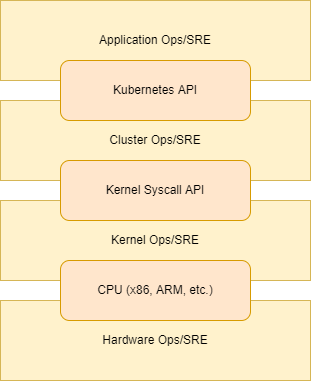

Abstracting Your Infrastructure

First, as we described previously, it seperates developers from specific machines. This makes the machine-oriented IT role easier, since machines can simply be added in aggregate to scale the cluster, and in the context of the cloud it also enables a high degree of portability since developers are consuming a higher-level API that is implemented in terms of the specific cloud infrastructure APIs.

When your developers build their applications in terms of container images and deploy them in terms of portable Kubernetes APIs, transferring your application between environments, or even running in hybrid environments, is simply a matter of sending the declarative config to a new cluster. Kubernetes has a number of plug-ins that can abstract you from a particular cloud.

Putting it all together, building on top of Kubernetes’s application-oriented abstractions ensures that the effort you put into building, deploying, and managing your application is truly portable across a wide variety of environments.

Efficiency

Efficiency can be measured by the ratio of the useful work performed by a machine or process to total amount of energy spent doing so. When discussing efficiency it’s often helpful to think of both the cost of running a server and the human cost required to manage it.

References

- https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/kubernetes-up-and/9781492046523/

Comments